Federal judges say their pay falling farther behind peers in legal profession Earlier this year, Martin Jenkins took what looked like a step down the career ladder. Jenkins traded his lifetime appointment as a federal trial judge for a seat on a California state appeals court.

Earlier this year, Martin Jenkins took what looked like a step down the career ladder. Jenkins traded his lifetime appointment as a federal trial judge for a seat on a California state appeals court.

In his new job, Jenkins must periodically face the voters, but he reaped one immediate benefit -- a 20 percent jump in his annual salary.

Jenkins' case highlights what Chief Justice John Roberts and many other federal judges have identified as an emerging crisis -- the failure to pay judges enough to keep them on the job and lure talented lawyers from private practice to the federal bench.

Not everyone sees it the way Roberts does. Committees in the House and Senate this year voted nearly 30 percent salary hikes for federal judges, but neither house of Congress acted on the measure.

Judges last received a substantial pay raise in 1991, although they have been given increases designed to keep pace with inflation in most years since then.

For 2009, though, judges are alone among federal workers -- members of Congress included -- in not getting a cost-of-living adjustment. Lawmakers get their COLA (cost-of-living allowance) automatically -- $4,700 for 2009 -- but they refused to authorize the same 2.8 percent bump for judges.

"Federal judges are currently under-compensated because Congress has repeatedly failed to adjust judicial salaries in response to inflation," said James C. Duff, director of the Administrative Office of the U.S Courts. "By its failure to do so once again, Congress only exacerbates a long-standing problem it must someday address."

Duff acknowledged that the current economic turmoil makes the judges' case harder. After all, federal trial judges are paid $169,300 a year, have lifetime job security and can retire at full salary at age 65 if they have 15 years in the job. Appellate judges make more, ranging up to Roberts' salary of $217,400.

But those salaries, large as they are, are much smaller than what judges' peers make in private practice. Attorney General-designate Eric Holder said his partnership at the law firm of Covington & Burling earned him $2.1 million this year. Attorney General Michael Mukasey, who retired as a federal judge in 2006 after 18 years, made nearly $2 million in 21 months at a New York law firm.

Timothy Lewis resigned from the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Philadelphia in 1999 at the age of 44, after eight years as a federal judge. Money was a consideration.

"It's almost embarrassing to say you can't survive on $170,000 or $180,000, whatever it was that I was being paid," said Lewis, now in private practice in Washington. "That's not true, of course. But it just did not seem conducive to the lifestyle I was trying to provide for my children in private schools and college tuitions, which I'm paying now." Appellate judges made $145,000 in 1999.

Yet even with the wide gap in pay between judgeships and private practice, only a handful of judges are leaving before they are eligible for retirement. In the past two years, seven judges younger than 65 quit. Of those, Mark Filip was appointed deputy attorney general of the United States. Another judge, Edward Nottingham, resigned amid an ethics controversy.

Jenkins, who did not return calls for this article, was confirmed as a California Court of Appeal judge in the San Francisco division in April, 10 years after President Bill Clinton appointed him to the federal bench.

Jenkins, 54, packed up his office in the federal courthouse and moved across the street to a state court building. The trip was worth $35,000 a year at current levels. Another Clinton appointee in California, Nora Manella, made a similar move in 2006.

David Levi also was a federal trial judge in California who gave up his seat and the prospect of judges' retirement pay in 2007. Levi became dean at Duke University's law school in Durham, N.C.

He was 55 when he left, with 16 years experience as a judge, but still 10 years shy of eligibility for retirement.

Levi said he left because of the opportunity to be dean, but thought hard about giving up his pension rights. "It was significant to me that I'd be paid more as dean of the law school," he said. "That made up some of the difference."

More important than retaining experienced judges is the growing possibility that lawyers will pass up the chance to be federal judges until their children are grown.

"I think we will see people who are prepared to be considered in their late 50s and early 60s, but who will decline to be considered earlier than that because it's too expensive," Levi said.

University of Chicago law professor Eric Posner questions the case for raising judges' pay.

Posner said if judges were underpaid, there should be trouble recruiting them in the first place and then retaining them.

"Existing judges could make more money if they retire, maybe three to four times their salary, and yet they don't retire in great numbers," Posner said. He recently wrote a paper with fellow law professors Stephen Choi of New York University and G. Mitu Gulati of Duke, raising doubts about giving judges more money.

Judges have better job security than almost anyone and good retirement pay, Posner said. "For many people, it's more rewarding and less stressful to be a judge," Posner said. His father, Richard Posner, is a judge on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago, and also skeptical of the need to increase pay.

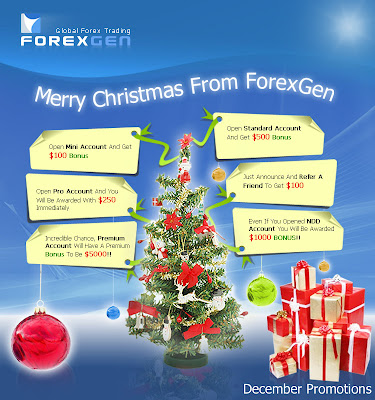

ForexGen offers three types of business partnerships:

*Introducing Broker

*White label

*Money Manager

ForexGen Introducing Brokers, White Label and Money Manager holders are recognized as a strategic business partners. The main focus of our service is to satisfy our partner's needs in order to deal with a qualified service and gain a huge income sharing plan.

[ForexGen] provide appropriate services satisfying the needs of all business partner's specified situation and requirements.

No comments:

Post a Comment